Afrobeat and Identity

Fela Kuti’s first album record cover

Image courtesy of the Wikimedia Commons.

Since the beginning of the Independence movement, to this very day, the African identity remains in crisis. Media, bombards the continent with massive volumes of foreign ideas and information, it is near impossible, to discern what belongs in the actual cultural context. The confusion is rampant, even blatant! Why importe concrete, when there is the mud brick? What use for a fork, if, fufu sauce never slips between fingers? The list goes on as African identity stumbles on itself, reaching for roots cast aside and, often erased completely by the legacy of colonialism. After all, “A tree with no roots, is no tree at all.” Yet, the African is still present and the culture -though at risk of waning- is still strong, so, why the confusion? The answer can be found through Fela Anikulapo Kuti, a manifestation of the ideals post independence leaders bring; Fela fervently exposes Africa’s most profound social issues, through deceptively subtle artistry, testifying his genius. The albums, Gentleman and Zombie, present two points of his immense character; the mind and the attitude. However, before diving into Fela’s mind and music, the cornerstones of the African identity deserve examination.

“Independence, free at last!”

On the 6th March 1957, the former British colony, Ghana, gains independence and a wave of excitement sweeps across the African continent (Nkrumah). A sub-saharan African country liberates itself from years of oppression and, a once distant hope is now clearly within reach as the independence movements accelerate. The symbol of the movement, and that moment is Kwame Nkrumah, the nationalist leader, and first President of Ghana. The moment itself, independence, is important in the way he declares it and, the manner in which he embodies it entirely for the purpose of this text.

He gives speeches, the night before and the morning after. In the night before, metaphorically speaking, he is a child, restricted; in the morning he, is a man, self assured, self determined, independent. The words he pronounces paint a picture of the gap he has now sewn together, between Africa and Europe, as equals. He pronounces “the warmest feelings of friendship and goodwill,” to foreign dignitaries, present, to witness the historic moment (Mensah). He bridges the gap between Africa and Europe, in a space that never before could be occupied, due to the chains of colonialism, understanding the attitude Africa must uphold. The decision to string the speeches across the two opposing days, in the National Assembly, is genius. Under nearly the same conditions; same audience, same room, same moment, an entirely new nation is born. What is most striking is not the moment of rebirth, rather how Nkrumah unpackages the power (to a lesser extent, absurdity) behind the idea of self determination. Nkrumah’s gesture is a bold declaration that the decision and ability to be free, has always been present, and a single tick of a clock being what decides that transition, only illustrates his point. This event resonates alongside Fela lyrics from the song, Colonial Mentality in which he states:

You don be slave from before, Dem don release you now

But you never release yourself.

Nkrumah provided hope unfortunately, events began to turn sour and reality began to settle, as across the continent African leader after, leader topples, including, Nkrumah himself. The narrative at first is clear, foreign intervention, but it is what happens internally that muddles perspectives. A prime example is the case of Patrice Lumumba, first Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Though Belgian authorities were the cause of instability in the DRC, it was not a Belgian, rather a compatriot of his, Mobutu, that oversaw his execution (Wallerstein). This infighting that occurs at the highest levels of African power, reveal the uncertain future that was unfolding before Fela’s generation. Such events serve as a total demystification of the hope and ideals that those like Nkrumah bring. Luckily, Fela needn’t look far for role models, his mother, Funmilayo Kuti, being the Pan-African woman. Reading Carlos Moore’s, Fela,This Bitch of a Life, paints a clear picture of the mentality Fela was exposed to and later employed himself. Through his anecdotes of his mother he makes clear; her energy, brilliance and especially defiance. In one very telling anecdote, his mother returns home, furious, and leaves in a man’s outfit, declaring, “it takes a man to fight another man!(Moore)” She shatters social norms and expectations to an extent that most -man or woman- would still not dare; today! If men like Nkrumah gave Fela a vision, a woman like his mother was certainly responsible for the drive and ability to do so. In another telling anecdote the two worlds collide; Funmilayo introduces Fela to a personal friend vacationing off the coast of Lagos, Kwame Nkrumah. Refusing to meet any government dignitaries, she asks him, “Ah, you come to Nigeria and you don’t want to see your brothers here,” to which he replies slyly, “I don’t deal with corrupt people.(Moore)”

Portrait of the Ransome Kuti family early 1940s

c. 1940

Image courtesy of the Wikimedia Commons.

Mind & Attitude

To get at what makes Fela’s persona tick, two qualities emerge, the mind and the attitude. Both qualities are embodied in the works, Gentleman and Zombie respectively.

Gentleman, released in 1973, is oh so deceptively simple and that is the brilliance of it and, the mind responsible for its creation. In, Fela: This Bitch of a Life, Fela declares “whatever I want to do is in my mind. That’s what knowledge is about. To be able to control one’s mind.” As emotions swing constantly and the underlying structure of the music swings the listener from one corner of emotion to the other, swiftly but never abruptly; control is evident. In the first few seconds there is a slow build up until the notes of a saxophone slice a thread across the music, and the listener is suspended, mesmerised by each and every note. Fela then drops us straight out the trance and into the beat; the body can’t help but sway, following the saxophone, the listener’s guide, across the intricacies of the melody. This total mastery of his craft already sets Fela apart, but then it is what he goes on to say that hits hardest. The lyrics are incredible for its ability to slice across issues without directly addressing them, in his own words:

Africa hot, I like am so

I know what to wear but my friends don't know Him put him socks, him put him shoe

Him put him pant, him put him singlet

Him put him trouser, him put him shirt

Him put him tie, him put him coat

Him come cover all with him hat

Him be gentleman, him go sweat all over

Him go faint right down, him go smell like shit

Though his words mock, his tone does not, it stays proud, in fact, it even pities, as Fela takes us through the dressing habit of this “gentleman,” clothing item after item. Doing so provides a suffocating effect, pointing out and making clear the many layers our gentleman dons. He repeats the phrase “him put him,” and with each repetition the temperature rises, so much so, that by the 8th repetition, the listener is under the impression of sweating with him. As Fela himself said “we go about copying foreign values, cultural concepts which permanently endear us to the whole world at large as certified slaves (Moore.)” The performance itself which would have been heavy with symbolism through gesture and presentation, would only have emphasised the message. Gesture serves to deliver the underlying message, an example would be in the song, “Water no get enemy,” in which the gestures and song resonate the gentle movements of a river. Fela combines this with the costumes and makeup they don, as the Chief Priest of the Shrine seeks to deliver a most impactful sermon. This serves to illustrate the intricacy with which Fela weaved his music and message. They are intertwined and no part overpowers the other, all is in harmony. What is clear with Fela is that, dance, rhythm, melodies, the music; is all secondary to the real art of Fela, the idea. To take the culture, confront it with the appropriate foreign influences and synthesise a new African culture; to accelerate, rather than replace his culture as the Gentleman does. African culture can and must proceed into the new era, confident of the place it can hold, and to do so requires self knowledge; roots. The melody, lyrics, and performance are merely ornaments to the much larger ideals he presents. Wole Soyinka, Fela’s relative appropriately remarks, “His music to many was both salvation and echo of their anguish...his life mission, to effect a mental and physical liberation of the race.”

Zombie presents another anchor of his character, the attitude; be stubborn! From Funmilayo to Fela, being stubborn is obviously in the DNA, and all for the best. Fela chose to be stubborn across very walk of his life searching his own truths, from the direction he took his life, opting out of being a doctor, engineer or other generics pressed upon him. When the military harasses Fela in an attempt to silence him, he only becomes louder! This is the attitude that pushes Fela to record Zombie, preceding the brutal attacks on the Kalakuta Republic, Fela denounces the military machine:

Zombie no go go, unless you tell am to go (Zombie) Zombie no go stop, unless you tell am to stop (Zombie) Zombie no go turn, unless you tell am to turn (Zombie) Zombie no go think, unless you tell am to think (Zombie)

Again repetition is a tool, not just to emphasise but also to tie it back to the military attitude, as he barks his lyrics with the overconfident tone of a drill sargeant. As we hit the chorus the horn blares from above, mimicking further the military mood. His lyrics illuminate not just the submissive attitudes present among soldiers in the military, rather deeper still; the neocolonial follower of attitudes, or zombie. The inability to question, and dig deep is what makes the gentleman into a zombie; no longer confusion but now a total absence of identity. In the face of crushing oppression by those he fights desperately to liberate, he returns stronger. To keep pushing against such immense opposition most would consider madness, but from Fela’s viewpoint; refusing to fulfil his goal and display his ewa, that is a sin.

All these things would be unachievable to Fela without a proper understanding of self, or to the Yoruba; iwa and ewa. Iwa, the essential nature of a person or thing, and ewa being the expression of it (Abiodun). For Ewa to manifest, Iwa must first be present, in Fela’s case this came in recognising where to direct his talents, music. As a man of Yoruba origin and as an African in general, he understood intrinsically; the art must go beyond the artist, it must be for his community, claiming; “If you want to do things because you want to be remembered, you are doing it for personal reasons only. Just do things ‘cause you believe in them (Moore).” These principles provide the solid backbone of culture upon which Fela mounts his legacy. The performances at the shrine then embody his appreciation of his own culture, as his dancers, the queens, reference deities, and natural phenomena through their varied and graceful array of motions. From the colours to costumes, every aspect of the production is a designed collaborative effort, and a unified front of Yoruba pride (Oikelome).

Fela embraces the legacies of his mother, Funmilayo Kuti, and other titans of the African continent, taking pride in the simple life, embracing the complexities of cultures, and pushing them far into the future. To young Africans he is an absolute role model; as most African parents keep funnelling their children down conventional paths, he is a reminder not to follow rather proceed confidently, the way the ancestors did before; independent.

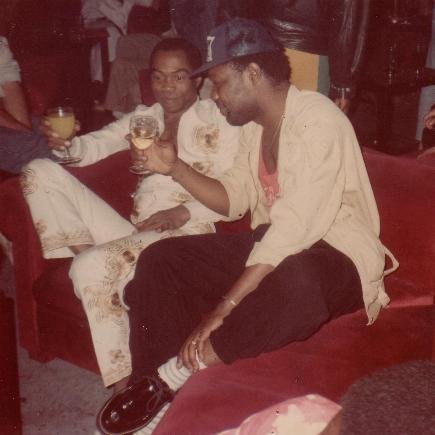

Portrait of Fela Kuti (left) and Waïpa Saberty.

Image courtesy of the Wikimedia Commons.

Bibliography:

Nkrumah, Kwame, Encyclopædia Britannica Inc, 2016.

Mensah, Eric O. "Pan Africanism and Civil Religious Performance: Kwame Nkrumah and the

Independence of Ghana." Journal of Pan African Studies, vol. 9, no. 4, 2016., pp. 47.

Moore, Carlos. Fela: This Bitch of a Life. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Publisihing, 2009. Print.

Wallerstein, Immanuel, and Dennis D. Cordell. Lumumba, Patrice, Encyclopædia Britannica

Inc, 2016.

Abiodun, Rowland. Yoruba Art and Language: Seeking the African in African Art, Cambridge

University Press, New York, 2014.

Oikelome, Albert. "performance Practice in Afrobeat Music of Fela Anikulapo Kuti." Journal

of Arts and Humanities, vol. 2, no. 7, 2013., pp. 82-94.

By Maxime Mballa-Tagny.